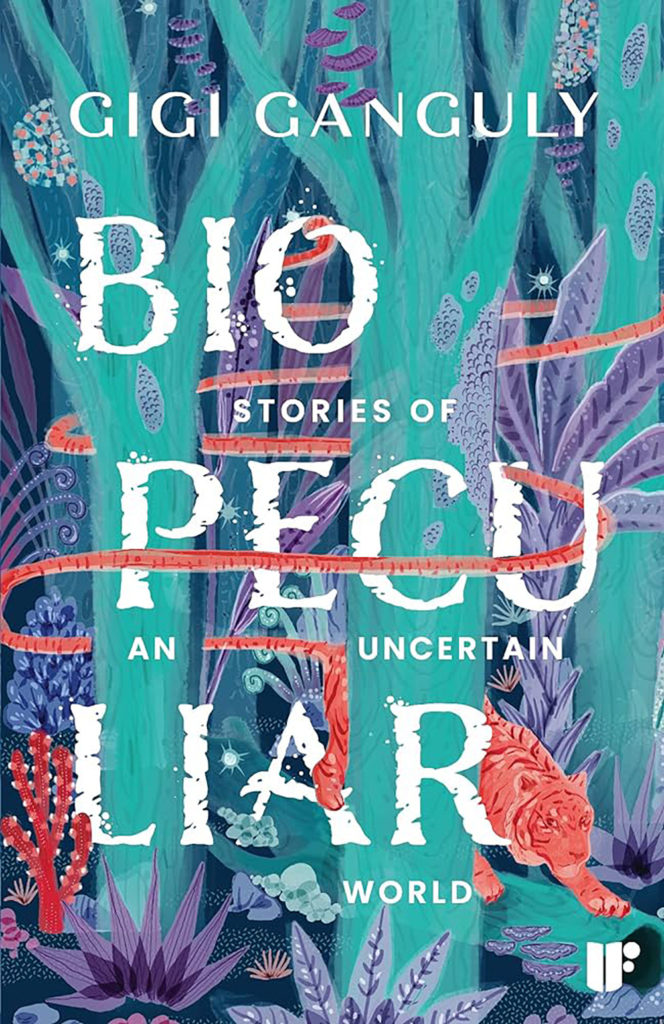

A man tends to his flock of clouds. A beehive’s queen finds herself threatened by members of her royal court. A woman sees messages in the murmurations of starlings. Gigi Ganguly’s Biopeculiar: Stories of an Uncertain World is a collection of twenty-two short stories that explore the natural world in all its weirdness and beauty, celebrating its strength while also reminding us of its fragility. Set everywhere from forests to the ocean to outer space, these stories are by turn laugh-out-loud funny, tender, and often completely surprising.

A follow-up to Ganguly’s novella, One Arm Shorter Than The Other, Biopeculiar is a delightful read for fans of the fantastical as well as newcomers to the genre. It is the first book published in Westland’s new speculative fiction imprint, IF, a first-of-its-kind endeavour in Indian publishing. Gigi Ganguly spoke with Helter Skelter about the inspirations for her short story collection, her love of wordplay, and treating nature with respect.

How did Biopeculiar come together? Did you conceive of it as a collection right from the start?

I was in Ireland for my Master’s in creative writing in 2018, and I stayed there for a year or two. I wrote my novella [One Arm Shorter Than The Other] over there. I came back home because of the pandemic. My family has a house in the Himalayas, and we were there while I was waiting for the novella to get published. So, in 2022, I started writing stories. In the beginning, I didn’t really have a theme in mind, about nature or animals, but I was surrounded by nature everywhere—there were so many birds all the time, and then there were the neighbourhood dogs. I heard stories about the tigers that used to live there, or there would be things that our neighbours said. For example, the idea for my story ‘Cocoon’ came from something that someone said. Once I had maybe four or five stories with me, I realised that there was a pattern of nature. I have a background in geography—I did my bachelor’s in that, and I’ve always loved clouds and climatology. So I knew I had to have a story about clouds, because I love them! I’d pick up ideas, I’d notice something in an article or in a book, and eventually I came up with ideas for these twenty-two stories.

How do you approach writing short stories? How is the process different from writing a novel or novella?

I actually find it easier to write shorter stories than the longer forms. Even in the novella, the first half was three interconnected short stories. I feel comfortable knowing that there is a very short start and an ending—the whole journey is quite short, and I have to fit in everything in it. I know that more than the beginning, the ending has to be really good. The kind of short stories that I like are ones where it’s not necessary for there to be a resolution—it can be slightly open-ended, but you should feel like you’ve seen everything there.

Some of the stories in this collection are laugh-out-loud funny, and some of them (like ‘A Year (Not Quite) Alone In An Alien Wilderness’) are very moving. Was that balance something that you were working towards consciously? Or was it more organic?

It was more organic. I didn’t really think that I should balance the collection as a whole, with serious and weird or funny stories. It just happened. For example, the dolphin story [‘Hats and Other Coverings’]—from the first time I read Waiting For Godot, I’ve always wanted to write a story that was basically just a back and forth between two characters. In my story, the two dolphins are doing that, and the three incidents that happen in the story, with killer whales, an argonaut, and a crab, are things that I actually read about online. Killer whales will actually toss salmon up in the air and put them on their heads. I realised that I could bring all these things together and make this very weird story, which doesn’t really have a message or anything, but it’s just fun. Of course, with other stories, I took a different tone. For example, in ‘Polarspeak’, even though there is a supernatural element, I still wanted there to be a slightly serious tone, because it is about the survival of one animal species. So I approached each story individually, and I just let it flow.

What was your process of research like for the book? Some of it arose from conversations or aspects of nature you were already interested in, but did it require any research beyond that?

Some stories came to me because there was this title in my head. For example, ‘Ceaselessly Sea Follows’—I just like the way it sounds, and it took me a while to understand how to approach it. In the end, I realised it’s best if I take the point-of-view of the sea itself and make it about rising sea levels, about tsunamis and environmental disaster. There were some stories like that, where I already knew what I wanted to do, and I wouldn’t say I did much research because I’ve already read quite a few articles about the topic and I knew the emotion I wanted it to have. There were other stories that needed more research, like ‘Call For Kelp.’ I knew that whenever a bomb is tested, the local human population as well as the animal population are affected. And while the human population is relocated, we can’t be 100% sure about the animal population. There must be so many small animals who get killed in the process. There was this podcast by a wildlife expert who was talking about this bomb-testing site somewhere in the U.S., where they actually relocated the otters. I read somewhere else about the importance of kelp, and the relationship between otters and kelp and sea urchins. I wanted to bring that into the story.

Most of the stories come from articles I happened to read, or podcasts I happened to listen to, or something someone would say. It’s only during editing that I would check—am I writing the right thing? In ‘Head In The Clouds’, there’s something about when the milk teeth disappear—I wasn’t quite sure about that. These technical aspects I did research, but the rest was stuff that I had already read about and got the story idea from.

There’s very efficient worldbuilding in your book. In ‘A Year (Not Quite) Alone In An Alien Wilderness’, in the first two paragraphs, you’ve set up everything about who the character is, what the world looks like in this future, and how it works. How do you approach world-building in these very short stories?

For this, I think I’d like to thank the years I spent as a journalist, because you’re taught that the first paragraph should tell you what the rest of the story is about. I think I learned it from there, that you should introduce, but also give a background to things. Since it’s a short story, you can’t just keep explaining and giving background all the time. Another thing I learned from reading so many novels, and when I was at the University of Limerick, is that if there are two or three characters, you can introduce background through the dialogue. This can be done in a way that it feels natural—maybe one of them doesn’t know something, and the other one knows. But again, it can’t be too much; it has to be natural. So that’s something that I keep in mind.

“The kind of short stories that I like are ones where it’s not necessary for there to be a resolution.”

One of the things that is so fun about your book is how you play with phrases and idioms. The idea that the phrase ‘murder of crows’ could lead to a police procedural set among birds; the phrase ‘queen bee’ inspiring a royal court setting populated by bees; even ‘barking up the wrong tree’ forms the basis for one story. Were these fun to play with?

That’s one of the things I enjoy the most—coming up with a title like ‘Barking Up the Wrong Tree’ and figuring out how I can make a story out of it. I love coming up with those terms, like ‘Call for Kelp’, as well. I think there were three or four other stories where I came up with these inventions, but I had to make sure that they didn’t sound all the same. I wanted them to be separate. That was something to keep in mind.

With ‘Corvid Inspector’, I just happened upon the fact that the [crow] family is called corvid, and I thought that just sounded so cool. If we just say “C.I.”, like Corvid Inspector, it sounds so official, like a real thing. While I was writing the dialogue at the first funeral [in the story], I realised that a group of crows is called “a murder of crows”, and when I looked up what a group of ravens are called, I think it’s an unkindness—and that’s such a soap drama dialogue to say back to someone. I had to add that. With the bee story [‘A Storm of Stings’], I wanted a title inspired by Game of Thrones, and I realised the bee society and their enmity with hornets would be a really good setup.

When people talk or write about nature there can be a tendency to overly romanticise it. But your book looks at nature in so many different ways. In some places we are taking on the perspectives of animals; in others, we take the perspectives of humans, where we’re not sure if the natural element is trustworthy. In other stories, like ‘Corvid Inspector’, animals are anthropomorphised. All these things coexist in your book. How did you approach how you wanted to write about nature, which is sometimes talked of as a monolith?

I’ve grown up with dogs my entire life, and I’ve got two cats right now. When you live with pets, after a point, you don’t really look at them as dogs or cats. You look at them as their own individual beings. I think it might have something to do with that, because I’ve always understood them to be their own individuals with their own characteristics, and their own completely different personalities and quirks. That’s how I approach all the animal characters, for sure, in the entire book. For example, in ‘Moss’, in the beginning, you might feel as if maybe the moss is evil. I wanted that—I wanted to show that if we are suddenly out in an unknown forest, we’ll feel scared for a moment, because it’s the unknown for us, but once we get used to things, once we understand each other, it’s really not that bad. And there is harmony. So that’s what I wanted to show, the harmony. Even though we might think that we are the superior race on Earth, and maybe we are in some ways, it’s not right to think that it’s just our planet. It’s everyone’s planet. That’s why I wanted to approach it like that.

I’d also like to mention Vesper Flights by Helen MacDonald, which is a book of essays. I really loved how she approached nature writing in those essays, because she was inserting her own experiences, her own feelings, into it. I’m not really a nonfiction person, but I love those essays, because you could feel that she loves nature, she loves animals, she loves birds. I wouldn’t say it was an inspiration for me, but maybe it was at the back of my mind, knowing that you can write about nature in such a way.

Like with Vesper Flights, were there other writers or influences as you were writing these stories?

With Vesper Flights, I’ve just realised it[s influence on me] today, right now, but it must have been there at the back of my mind while writing! Also, Travels with Charley by John Steinbeck. You think of John Steinbeck, and you think, serious, like Grapes of Wrath. But when you read Travels with Charley, you realise that the man was so funny, and he loved animals, especially his dog, Charley. He basically journeys across America, I think in the ‘60s. They go to the Redwoods, and there’s this section where John Steinbeck wants his dog to pee on a Redwood tree, this huge, massive tree, but his dog will not pee… I don’t remember what happens in the end, but there are so many of those funny moments. There’s also a section where he talks about people who infantilise dogs, people who say, “Oh, they’re so cute,” and he says, “Dogs should be respected.” He’s very serious about that; he’s treating his dog like an individual, like a separate person, in a sense. So that, again, must have been at the back of my mind.

If we talk of short stories as a form, Ted Chiang is someone that I really love. His stories are amazing. They might not be about nature, but I like the way he frames stories. ‘Story Of Your Life’, which Arrival, the movie, is based on, is to me the best short story ever written. He captures your attention, and he inserts such emotions that you will cry at certain points. There is some humour as well. I also love the fact that the main character is a linguist—you don’t really come across linguists; if it’s an alien invasion story, it’s usually the military which is at the forefront. Just as an inspiration for writing short stories in general, I think Chiang someone that I really look up to.

Biopeculiar is the first book in the new speculative fiction imprint from Westland, IF. What was your journey to publishing with Westland? How do you feel about your book being the first in this brand new imprint?

The fact that my book is the first one is the most amazing thing ever! Sci-fi and speculative fiction are more of an American thing—that’s the major market. In India, publishers might publish speculative fiction once in a while, but there’s no dedicated imprint like this. I’m extremely happy. Karthika [V.K.] and Ajitha [G.S.], my editor—they’re both really good. I don’t have an agent—once I was ready with the collection, I basically emailed everyone. Around that time, I was nominated for the Subjective Chaos Kind of Awards in the novella category, so I think that might have helped me. I just sent out that email and Karthika asked me to send out the full manuscript. That’s just how it happened.

Tell me about how the covert art for Biopeculiar came together.

I actually had a Pinterest board just for book covers. I had sent that to the publisher, saying that these were the kinds of things I like. Bhavya is the one who illustrated the cover, and she came up with three or four options. When we saw this one, we thought, “This is amazing, we have to go with this one!” Incidentally, I realised later on that this cover has a teal colour, as does my novella. So it was meant to be.

What is your writing process like? Do you have a daily writing practice?

I do try to wake up really early, around 6-ish, and write before office hours. Once office is over, you don’t want to look at the laptop again! So on weekdays that’s the time, and on weekends, if I’m not watching K-dramas or Monk, I try to find some time to write. I do write short stories once in a while, because I have a bank of maybe forty short story ideas. But I want to tackle a novel first. I feel like because I’ve done a novella and a collection, I should do a novel now, and then I’ll come back to short stories again.

Right now, I’m working on a novel which is going to be about artificial intelligence and consciousness, and it’s going to be super futuristic. I don’t want to say which T.V. show, but one of the chapters is inspired by one of my favourite shows. Once it comes out, people will be able to tell which one it is. Another chapter is inspired by the landlady I had in Ireland, who had a dog. I grew up in Delhi-N.C.R., and every kid in Delhi-N.C.R. will go to the science museum at some point, so I wanted to include that in a chapter, so that is also somewhere there. The rest of it is me thinking what would make sense in the future—in the present day, what are the most important things in India, and how would that evolve in the future?