We live in an age of instant gratification. We want things now, and we’re willing to bypass simple human contact to get them. The ‘instant gratification’ story is sexy; it’s what ‘sells’. That’s all well and good, but when folks get home and realise that things are not happening as fast as they expect them to, they give up before they get going. And that’s where most get tripped up.

Ritika Mittal offers a refreshing change from mainstream commercialism. She speaks to us about being an innovative entrepreneur working with textiles, weaves, colours, and patterns to produce designs that are fresh, current, or even ahead of the fashion curve. The term ‘instant gratification’ doesn’t figure anywhere in her ‘never say never’ quirky, offbeat, and infectious attitude. Here’s why—

MORA’s Ritika Mittal with some of the weavers that she works with.

April 2009: you’re 25 years old, working as a television producer for a reputed channel on one of their biggest shows, and you decide to give up years of professional experience to pursue your love for fabric, colours, and design. And it all started with a wedding. Elaborate.

I spent more than a decade working in the media industry working on documentaries, reality television, and other shows. When my wedding was around the corner I was very sure I wanted to stay away from the boring, regular, bling wedding outfits. And I knew I wanted to wear cotton at my wedding. Unfortunately ‘good’ cotton wasn’t readily available and after a lot of searching and incredulous ‘What?! Cotton wedding saree!’ exclamations, I decided to design my own saree. Finally it came down to the perfect mulmul saree—I loved it and so I decided to design it. An instant hit. This triggered off a love for organic fabrics and combining colours and patterns.

You frequently write blog posts about the love and support that you receive from your family and friends. MORA was all about gut instinct. What did yours tell you?

I never thought I’d design another saree, but somehow textiles and fabrics didn’t seem so ‘foreign’ to me anymore. So one day I decided to go to the handloom market and I randomly picked out 10 fabrics for 10 sarees. I made elaborate designs on paper, bundled up the fabric material and sent it to my mom in Punjab. And the most amazing thing happened. My mom totally connected, she got the tailors to stitch the designs just as I envisioned them from those paper designs and bundles of material. When the 10 sarees were finally ready, she sent them to me in Mumbai, packaged in three huge bundles. I was still working in the media industry and the parcels came to my office. Those were the first MORA pieces, ever. I felt like a school girl giggling as I ran into one of the office bathroom cubicles with a friend to tear open those parcels. When I saw the 10 sarees—each so special and unique—I just knew this was it. This was my calling.

Contrary to what Shakespeare said, in your case it’s all about the name. Unravel MORA for us.

So I had these 10 fabulous sarees, each so unique that I knew one thing for sure! I would only work with organic fabric and would never repeat a design. MORA was born in an auto (giggles). I was travelling with my husband Aditya and was telling him how these sarees were my designs brought to life by my people—the name ‘MORA’ (meaning ‘just mine’) seemed the most natural fit. I spoke to my best friend (who had a habit of doodling) and she came up with an eye/bindi and a tree. It all just fell into place. ‘Mora’ also means peacock. So now I had 10 beautiful sarees and a logo/name ready. Mora. (Smiles)

Mumbai is a city where all major brands are available in chic, suave malls and retail clothing chains, apart from niche attire brand outlets. A reality of obvious commercialism. Several such boutiques offered to ‘stock’ MORA designs. And you proudly but gently refused. Explain.

My sister-in-law loved the sarees and suggested that I connect with a lady she knew in Vizag. In February 2009, I created a private Facebook album with the pictures of the 10 sarees, each with their own name, identity and details. Eight of the 10 sarees were immediately bought. I neatly packaged the saris with the MORA tag and parceled them to Vizag. This incident taught me a very valuable lesson. I didn’t know who bought these eight sarees and that really upset me. Each MORA piece had so much work, dedication, and love that went into them, it just felt right to connect and build personal relationships with others who connected with the fabrics, colours, and patterns MORA brought to life. I decided I would never retail to any store. Because each piece has such personalised attention to detail, it’s impossible create more than a certain number. Love for work, fabrics, textiles, weaves. The ethics of MORA. There is no mass production. MORA is not work for us. MORA is our life.

The designs happen out of a beautiful apartment in Malad. The fabrics are sourced from across the country, stitched together in the family home back in Punjab, and parceled across the globe. And all of this happens without the four-walled confines of a commercial ‘selling’ space/boutique/shop. Were these conscious decisions or did all these just seem like the most natural choices?

MORA happened because my mother connected instantly with elaborate designs on paper and bundles of fabric which she brought to life. To convince my mom to believe in herself—instead of ‘this is for Ritu’ to ‘I am doing something‘ was very crucial. When I opened those three parcels with the 10 sarees, I realised my mother’s potential and I knew this is what I wanted to do—I was done with media. What my mother brings to MORA no four-walled confines of an office/boutique/shop will ever offer. It’s a logistical nightmare (laughs). I travel across the country sourcing fabrics, weaves, patterns, and colours, the designs are sent to Punjab to be stitched and then parceled across the world. There’s absolutely no logic to the madness. But it’s happiness. Punjab is where I grew up, Mumbai is where I met and married the love of my life Aditya and the northeast is my calling.

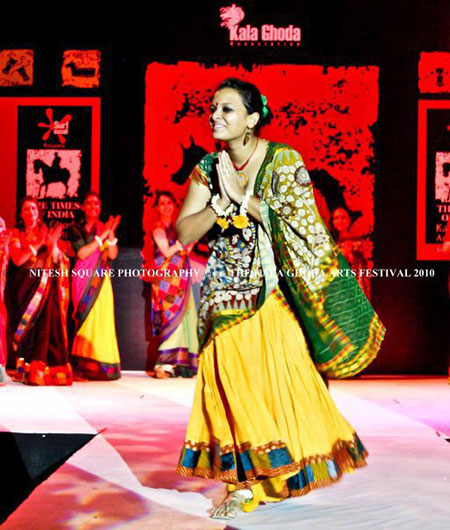

Ritika Mittal at the Kala Ghoda Festival in Mumbai. Photograph by Nitesh Nitesh.

The northeast. Going there is one of the biggest decisions you’ve ever made and it changed your life completely. Frantic emails to friends of friends of friends and countless Internet searches were involved in your determination to make a trip. And of course, there was your exasperation at how ignorant we are about our own country. But you made it and spent a delirious four-and-a-half months in the remote parts of Assam, Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Manipur. Weave us through this journey.

During day three of the Kala Ghoda Festival [in Mumbai] one of my buyers asked me, ‘So, what’s next?’ And I just blurted out to the incredulity of my husband Aditya, ‘The northeast’, and then I started my research. The textures, weaves, and colours of the northeast took me completely by surprise and I knew I had to go there. It was meant to be. And it’s been two years since my first visit. I discussed this with my family, who were flummoxed by my determination. I got to Delhi and did more research—the craft council, ministries, and other than the famous fabrics there was not enough information. I just had to do it myself. I had a few names and numbers of absolute strangers, who turned out to be my best friends in the northeast. They invited me over and the only assurance that they gave me was that it would all be alright. That was reason enough for me to make my own journey. I kept moving. The problems in the northeast are more external than internal. Due to the universal awareness of child labour the tradition of children learning how to weave cotton from a young age is no more. Everything is synthetic. I travelled from village to village in my endeavour to bring back the traditional cotton weaves. People became family. The infrastructure is so weak that I need to keep going back. My travel takes me to more and more remote places for the love of textiles; the search for colours, patterns, weaves, and wonderful people never ends. The northeast is neglected when it comes to textiles and I want to bring back traditional weaves on cotton to combine with cuts and fabrics of various states. Wherever the road is less travelled, I will travel there.

The dedication, talent, and most importantly the support of the tribal weavers and rural artisans is what MORA is all about. Blogs, photographic calendars, thousands of pictures, and every single MORA creation speaks volumes of your cause. Tell us more.

I have a lot of love for textiles and people—MORA connects with both. Synthetic fabrics have taken over the textile market, causing health problems—mostly skin issues. MORA aims to bring back the traditional weave on cotton. We want to experience the lives of the artisans, live, and surrender to the people.

Without being commercial, MORA is truly a commercial success. You must be so proud in all your humility. You also provide a means of livelihood for the real workers and the authentic talent—the weavers and artisans. What would you like to share with our readers about believing in yourself, following your dreams, and knowing when to say no?

MORA has never been about the sales or the fancy marketing and packaging. I have never aggressively pursued buyers—this is not a buying and selling proposition. It’s all about my love for textiles, and forming a connection with tailors, artisans, and buyers. We don’t work on deadlines. We have learnt to say no because it’s never about the money. I am living my dream, how many are able to do that? I live by the three MORA ethics—never retail, never repeat a design, and always build personal relationships with your artisans and buyers. Connect. Live. Be Happy.

———

Visit the official MORA web site at this location.