New husbands are like burrs: they stick, they irritate, and they’re mostly unwanted. Mine turns to me and says, “Do you know that Gangtok is the only part of our country from where you can see another country?” He beams at me as though I’m a gift he doesn’t deserve.

I understand now why we’ve come here, so far from Mumbai, for our honeymoon, although I’m certain there are other closer places in India from where one can see foreign countries. I don’t say this out loud, of course, for even I know that a woman must choose her battles carefully in marriage. Besides, I’ve been married for only four days and know my husband the way a student knows a professor, with familiarity but no intimacy.

Nikhil’s smile has the full force of his teeth. I smile back as though I’ve won a battle I didn’t know I was fighting. One compromise down; 9.999 million more to go. Is this just the beginning of marriage?

I’ve been seized by this life force that is pulling me and pushing me, tugging at me, without letting me rest. Everything has changed, yet nothing has changed. I’m still breathing, sleeping, bathing, and eating in the same way. Where’s that sense of life-altering destiny, that huge shift which I spent most of my life waiting for?

I look outside. The Sumo we’re sitting inside is snaking its way past the mountain to Nathu La Pass. The mountain is on one side of a narrow road that drops into a deep valley. There’s place for only one car on this treacherous road, yet every minute or so a car edges its way towards us. Just when I think it’ll topple over—and my jaw clenches—it splutters past. I’m glad that we have the solidity of the mountain on our side, but I worry about the rosy-cheeked children in these cars, wearing their multi-coloured sweaters, nibbling desultorily on alpine cheese, black seeds from passion fruit stuck to their mouths. Do they not see the sheer fall and the shining pine trees, poking out like teeth from the valley below them, ready to stab and take out their little lives? Do they not see the mountain open and close its jaw?

I see a small prayer wheel on the dashboard spinning round and round, calm, a blessing. I close my eyes and take a deep breath.

Last night, Nikhil had put a bamboo tumbler to my lips. The Tongba slithered down my throat like a porcupine wriggling its way into a hole.

“Is this alcohol?” I coughed.

He mistook my question for an accusation and defended himself. “It’s fermented millet. I thought it would relax you.” Then, quickly, “Please don’t tell Mummy-Papa.”

The last thing I wanted was for my conservative in-laws to know that I drank. I nodded. Our eyes locked in compliance. This was our first secret as husband and wife. The Tongba tasted buttery enough to finish. The burning in my stomach turned into something soft. I could hear the hum of the electric current feed the naked heater in our room.

“Your eyes are big, so innocent, twinkling like… stars in the sky,” Nikhil said to me with a slur. I giggled. Emboldened, he put his hand on mine. It felt different. His touch, cold and unfamiliar, was nothing like Kabir’s. “That’s what I love most about you. You’re untouched, like a flower that hasn’t bloomed.”

His unimaginative compliment made bile rise in my throat. Some people savour the fire, while others get burnt. Nikhil’s matrimonial ad had asked for a ‘convent-educated homely girl’, a.k.a. virgin. I’d read more such ads than the hair I could count on my head. I’d met many such men, seeking virgins, and told them about my Kabir and my one abortion. It was the twenty-first century, goddammit! They ran, each and every one of them, and left me an unmarried, thirty-one-year-old, childless woman; virtually a crime in India. So I learnt what every woman eventually learns, to never reveal her past or bra strap.

By the time I met Nikhil I was too weary to show my true self. All I wanted was to roll into one pocket of the roulette wheel of arranged matches and stop my head from spinning. Besides, Nikhil was not a lout, a drunk, a loafer, or a smoker. He wasn’t smelly or hairy. That was all I needed from a man.

When life doesn’t give you what you want, you learn to live with what you get.

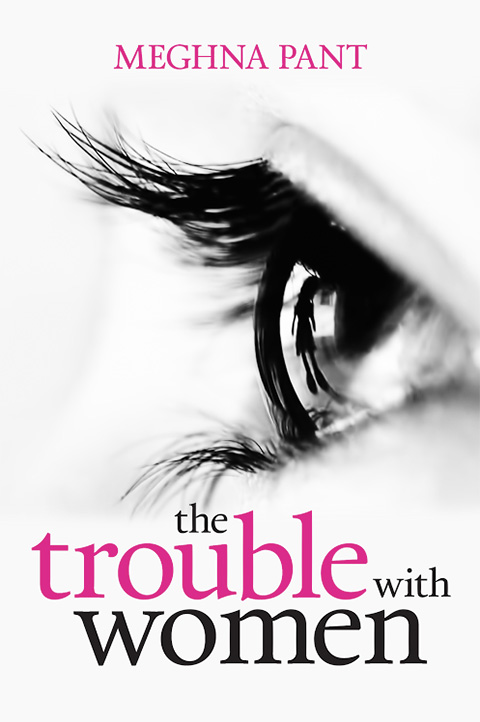

(Excerpt from The Trouble with Women by Meghna Pant. Purchase the book using the Juggernaut app.)