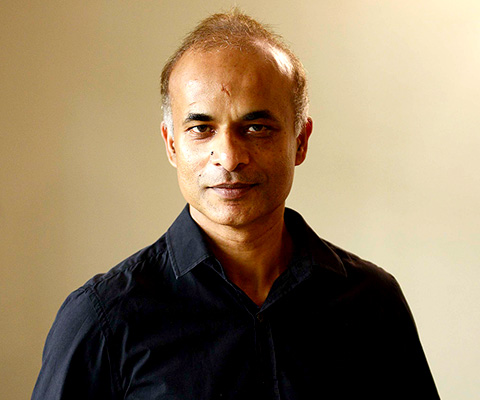

It is easy to be indignant about Manu Joseph, if you have read his columns. He believes that farmer suicides are less a factor of poverty than depression; that 99% of Indian men have far fewer opportunities than many urban Indian feminists; and that the pursuit of happiness is a futile aspiration.

The headlines may sound sensational, but he uses wicked logic; the same logic he often uses to take on India’s Left. With the Right, he seems to require lower levels of cerebral effort. He talks much like a new-age philosopher (he would detest that label, of course) armed with ample humour, a humour that derives from the simple absurdities of life.

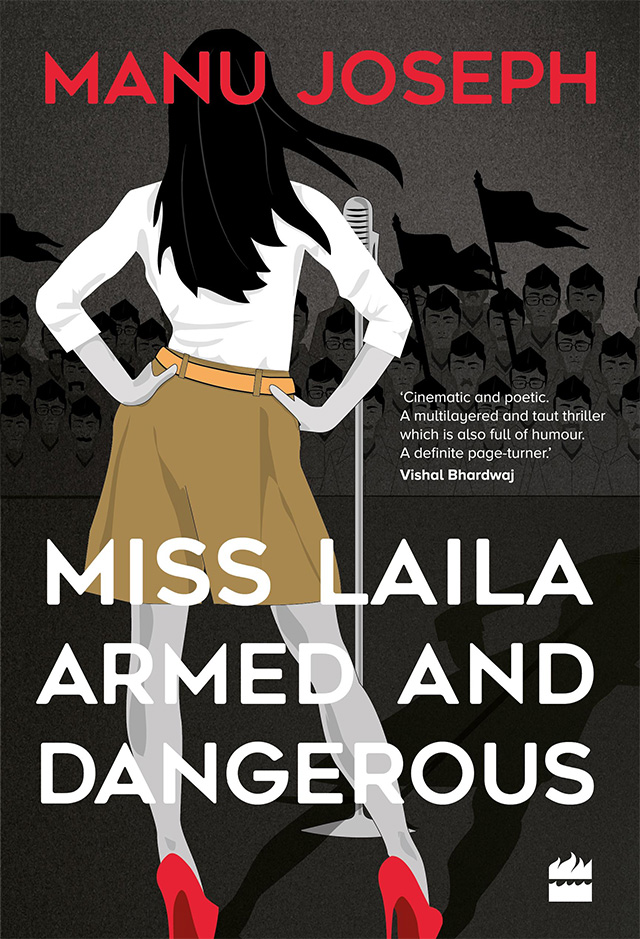

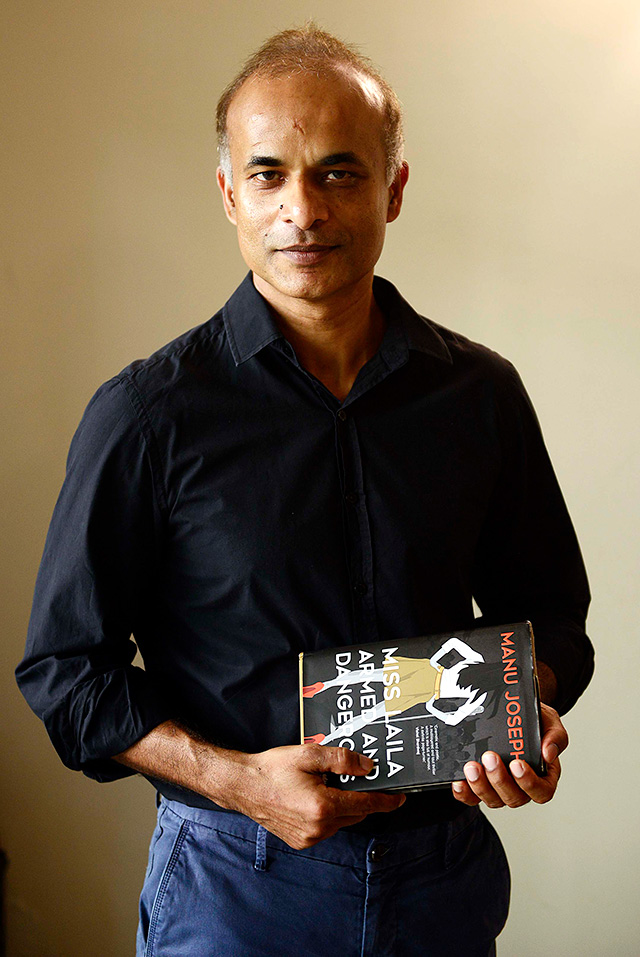

It is hard to decipher his agenda, although I have been tempted to think of him as a contrarian. Like the protagonist Akhila Iyer—an unimaginably witty athlete and neurosurgeon-in-training—in his latest novel, Miss Laila, Armed and Dangerous, Joseph is a prankster of sorts, but not devoid of political purpose.

Read on for excerpts from a recent Helter Skelter interview with the author—

Manu Joseph: “Clarity is happiness and intelligence. My pursuit, through writing, is only personal clarity.”

Akhila is a rather interesting protagonist, a woman unlike any we have seen in Indian fiction. But did she need a backstory with an activist for a mother—a Maoist enabler—which resulted in an absence of stability and love to make her quirkiness convincing? I guess what I am questioning is if it had to evolve from a place of helplessness.

You might be surprised to know that the questions you raise were something I had myself. Should I show why Akhila is a prankster? I knew why she was, but should I show it? When we read about student unrest in our country we know that it is usually the humanities students who are agitated. Some of us may have wondered, ‘Don’t science students have any problems with life and nation?’ I read a view of a humanities professor, who argued that the arts students agitate because they are more socially conscious and more compassionate. This is bullshit. Science students are, very simply, busier. Also, they have more to lose.

Akhila is a student of medicine. She has taken a year off, that is why she is able to focus on her pranks on activists. Pranksters need no reason to play pranks, they are just wired that way, but in Akhila’s case there is a deeper reason. Her mother was of a type, the very righteous type she plays pranks on. This faultline is important for us to forgive the prankster or to see her as a political person. This the observation of the Hindu ideologue—that she is not a comedian, she is something else, something political. Being political is a personality type. They are serious, that is what they are, they are the serious type. They take everything seriously. They only use humour as a form of violence.

You challenge the degree of goodness in the good, and evil in evil. Do you ever think about what position you write from?

Pure goodness is probably genius. But mostly it is something more interesting. There is a form of goodness that is actually a form of evil. In my experience as a journalist, I have seen sadists hiding in places of empathy because they need to be close to human suffering, they need to be in the best seats to watch human and animal suffering. They are fascinating. They themselves do believe they are good. Then there is another form of good, which is a form of nuttiness, like Mother Teresa’s. It does not emerge from clarity but from delusions. It may have its uses, but they are often overstated. Then the garden-variety good is an organised industry. I often referred to it in my journalism as organised compassion, which is a form of employment. As it is governed by subjectivity, in every society, the elite have a monopoly over it. Writers, academics, art entrepreneurs—they control this form of goodness. They are there not because they are the best, but because they had the best social networks. When the guardians of virtues are feeble, various other mental states in the society, many of which might be a part of evil, succeed. Now you are asking me whether I identify myself with the feeble good or the psychiatric evil. Naturally I am going to say that I am on the side of sanity. Clarity is happiness and intelligence. My pursuit, through writing, is only personal clarity.

When you began Miss Laila, did you intend it be political satire? Does that preliminary bracketing make it easier to develop a narrative style for the novel?

I wanted to get into the mind of three people: a posh prankster, a little girl who adores her older sister, and a poet who is given a unpoetic task, like shadowing a terror couple. The rest of it—the politics and all that—is by the way. A novel is always about people, and very little about the labels they give their actions.

Most of your female characters have transcended the oppression of their circumstances by the gift of eccentricity, but there’s a certain pathos around the men.

I create the women in my novel by deriving from the women I like, so they perhaps have overarching characteristic traits. That reminds me that I should really give straight hair to my female characters as the frequent spiral curls are begin to annoy some of my readers. As for the men in my novels, I think they are more amused by the world around them. Such an amusement might have the quality of pathos but it really is amusement.

Was Miss Laila in some elemental way inspired by A Case of Exploding Mangoes? I couldn’t quite shake off that feeling through the novel.

I would be delighted if readers are minded of A Case of Exploding Mangoes when they read Miss Laila, but no I was not inspired by that book even though I liked it very much.

There’s very sharp insight, psychological in nature, that surfaces in your novels—in The Illicit Happiness of Other People in particular, but even in Miss Laila. Do you create characters around the crystallisations you arrive at about the world around you? Because, in fiction, we’re always asked to imagine the world through the characters, and that sequence doesn’t seem true for you.

In the formation of a novel there are several strands of plots and characterisations and objectives, and also there are these nuggets which are observations, biases, grouses, expressions of adoration, memories. They do not need plots and characters, but in a novel, like in a balance sheet, everything has to be accounted for and they have to go somewhere—into someone’s mind. In fact, the primary objective behind writing a novel might be that one moment, or one paragraph. You then weave other minor objectives around this. It’s strange how a novel forms.

There’s the recurrent trope of the dysfunctional family in your novels, which shapes the central characters. Where’s that coming from?

I really do believe almost all families are dysfunctional, it is just that some know it.

Can there be subtle activism underlying a good story? I’ve always felt that about Serious Men.

In a story, we must not confuse the persistence of justice with activism. I can clearly see why you feel there is an activist strand in Serious Men. The protagonist is a Dalit, a social underdog, and he has to pull off a difficult trick—to make the world believe his son is a genius, when he is not. We are all with him because he is poor and smart. But the larger point I wanted to argue is that extreme intelligence is a probability, hence it can be anywhere, it can be in a chawl. So, what appears to be an activist strand in the novel is actually the opposite—an ode to the strong, to strength, to cerebral upperclass. But I do agree that morality is an exquisite plot device. It is from morality that we derive the best form of movement in a story. All storytellers who have tried to challenge the value of morality in storytelling are doomed.

Who are the writers, the stories that have influenced your own?

I am not influenced by anyone but I do like some people. Various parts of my novels are influenced by various things, simple things, objects and moments.

I attended a recent event you spoke at in Mumbai, and you had strong views on the journalistic establishment; particularly that there’s a lot of activism masquerading as journalism. What would you label the nature of your columns for Mint, and before that, The New York Times?

I do not question the fact a bit of moral tension is encoiled in writing, especially journalistic writing. What I object to is the elevation of outrage, self-righteousness, and posturing as high journalistic qualities, and the casting of storytelling and entertainment as subordinate to the farcical proclamations of a writer’s nobility. Journalism is primarily storytelling, everything else only follows from there.