Dusk, says Saki, is the hour of the defeated. Harried men and women, who have fought and lost life’s battles, come out in this half light so that they can hide their misfortunes from the scrutinising eyes of those who inhabit the realm of bright lights and cheerful laughter, the land of hope and glory lying just beyond the sheltering shade of droopy shoulders and disappointed eyes.

Though such a meticulous murder of one of the most phenomenonal hours of the day demands a categorical reply, I shall reserve it for a later date, concentrating at this hour on recounting an episode when such a setting not only stimulated my intellect but also numbed the more primal of my instincts. And that, my friends, happens very rarely.

About two years ago, I had shared an exceptional Delhi dusk with a lovely companion on an unremarkable bench in a nondescript park situated somewhere close to the bevy of lights that is one of the favourite haunts of the rich and fashionable elite of the city—the M-Block Market in Greater Kailash. The lamps had, in due consideration of my repressed desires, refused to come on and the handful of over-enthusiastic joggers were in a world of their own, oblivious to any misdemeanours on my part. Although my companion had fixed her stare on a faraway tree and looked sufficiently poignant, I was quite aware of a third eye that was making a mental note of all the uncalled for expressions that were playing a game of carrom on my face.

The Mahabharata is replete with cases of charitable Brahmins impregnating obedient (though often not willing) queens in order to oblige heirless kingdoms.

In such a romantically charged setting, I thought it opportune to unburden myself of my thoughts on such diverse subjects as Che Guevara’s brand of communism, Niyoga, and the greatest story ever told, the Mahabharata. As my companion patiently bore this brutal assault on her patience, her reluctance to be challenged intellectually and her eagerness to plant the proverbial slap across my face was, fortunately, lost on me in that hour of gloaming. And as my verbal diarrhoea splattered itself across several continents and millennia, the exasperation of my escort reached a crescendo; till she could no longer feign ignorance and politely suggested that it was getting too late.

Reading the very readable Dusk by Saki, I revisited that evening and realised how a more fashionable man could have very easily had the face instead of the palm. However, the subjects of our conversation interest me equally even today and I am forced to wonder if I wouldn’t regale another unsuspecting victim with the same practised banter. So, without further ado, let me find out if my efforts at rekindling the poor readers’s interest in one of those archaic subjects cause them to itch for revenge every time they find themselves sharing a grey dusk with another pseudo-intellectual or if they choose to forgive me for putting them through such a gruesome ordeal. Ahem.

Niyoga, literally meaning delegation and known in some frivolous circles as wife sharing, is an ancient Vedic tradition wherein a woman, whose husband was incapable of producing an heir by reason of death or impotency, would request and appoint a person for helping her bear a child. As per Manu Smriti, the man chosen for this task should either be an immediate family member, such as the husband’s brother, or a highly revered member of the society, such as a Brahmin or a Deva. However, there was a lot of fine text enjoined under this practice. The couple could not engage in the sexual act for the sake of pleasure since this was an act of Dharma, implying an impassive and emotionally detached union. The infant thus born was referred to as Kshetraga and considered the child of the husband-wife and not the provider of seed. Moreover, the appointed person could not seek any parental relationship with the child in the future as he was simply fulfilling his duty or Dharma. However, just in case a poor man’s temptation got the better of him, the Vedas also lay down that no man can perform Niyoga for more than three times in his life.

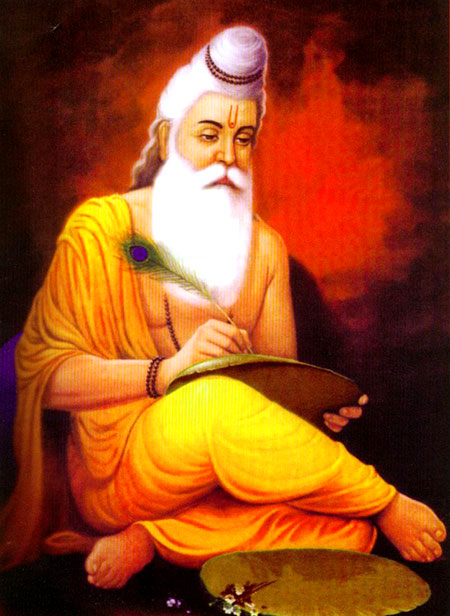

Our friendly religious epic, the Mahabharata, is replete with cases of charitable Brahmins impregnating obedient (though often not willing) queens in order to oblige heirless kingdoms. So when Vichitravirya died without any sons, his mother Satyavati approached his half-brothers to do the needful. But since Bheeshma had already taken the terrible oath, the task fell upon Veda Vyasa, Satyavati’s son from before she was married to Shantanu. As a result of this coitus, Pandu, the pale, was born to Ambika, who had turned white out of fear, while Ambalika bore the blind Dhritarashtra, apparently because she had closed her eyes after seeing the formidable form of the sage. Even after the passage of an entire year since neither Ambika nor Ambalika were willing to have a second go at Vyasa’s famed sexual prowess (I wage a lonely war in sticking by this conclusion), they sent a maid in their place, who gave birth to a healthy Vidura.

The practice is not unique to Hinduism or India and the somewhat similar tradition of levirate marriages—Yibbum—is mandated by the Torah wherein a brother is obliged to marry the widow of his childless deceased brother, with the first-born being treated as the heir of the deceased brother and not the genetic father. However, if either of the parties chooses to opt out of the marriage, both are required to go through a ceremony called halizah, wherein they publicly renounce their right to Yibbum. The rite involves taking off of a brother-in-law’s shoe by the widow whereby he is symbolically released from the obligation to marry her and she is free to marry whomsoever she desires. Most Jewish communities have seen a gradual decline of Yibbum in favour of halizah. A similar custom is, nevertheless, still prevalent in some parts of Punjab and Haryana where it is known by such names as “Latta Odhna” and “Chadar Dhakna”.

As with all such religious customs, it is quite easy to see that it is convenience rather than divine will that dictates such norms. So while Niyoga allowed a king to produce a legitimate heir and keep the genealogical tree alive through slightly suspicious means, with women being relegated to very restricted roles in most agrarian societies, practices like levirate marriages insured that the ancestral property would remain in the family of the deceased. Moreover, inheriting the wife also meant that the children, if any, would be taken care of, something that couldn’t be taken for granted were the mother to marry a complete stranger. It is ironic to note that the very texts that fundamentalists quote from in order to champion their constricted understanding of culture and heritage also make them fall flat on their feet. For even if these epics were produced by divine decree, they reflect the prevalent customs and traditions at some point in our history. Who are they, then, to uphold one ‘culture’ and decry the other?

“For if Arjuna was not the greatest archer in the world, who was he?”

Niyoga is just one specific example but the reason that I remain hooked to the Mahabharata is its mercilessly questioning tone, a cruel sense of irony, and the moral ambiguity that plagues almost all its characters. I believe that it is this very moral grey zone that has allowed modern story tellers to recount the tale from a perspective that is distinct from the all-knowing one. No wonder thus that in Kamala Subramaniam’s rendition of the epic, Duryodhana is portrayed as a Shakespearean tragic hero, doomed because of a fatal flaw in his character—his hamartia. Even Yudhistira, when he eventually becomes Dharmaraj, does so “not by divine right but by slowly, painfully accepting the many weaknesses in his character and finding ways to overcome them”. Stripped of this divine aura that has threatened to cloud its message, the epic might actually have more to tell us than what we bargained for.

Unlike the Ramayana, the Mahabharata does not come across as a well defined battle of good versus evil. Iravati Karve, author of the exceptional Yuganta, writes that the original Jaya was one of the “last examples of pragmatism in Indian literature, something that was consequently lost in the dreamy escapism of Bhakti tradition”. If I were allowed to be a little more spiritual, I would probably say that understanding these dilemmas and making sense of them in the context of my own life is perhaps the motivating force behind all my reading on this subject. The questions of self-doubt, identity, and duty—all so crucial to a thorough understanding of this ancient poem—are just as significant today as they were four thousand years ago. Religious bigots might try to interpret the text in order to suit their narrow purposes but the concept of Dharma, which is the heart and soul of the epic, “is not only untranslatable, but the Mahabharata’s characters are still trying to figure it out at the end”. All we can do is learn from their efforts so that we do not fritter away our lives reinventing the wheel.

wow. nice read.

You are obviously into the wrong chicks.

Loved the piece, by the way.

Bad decisions always make for very interesting stories :)

By the way, thanks!

Hah. That’s like something I tweeted recently: Bad experiences make for interesting stories. :)

: )