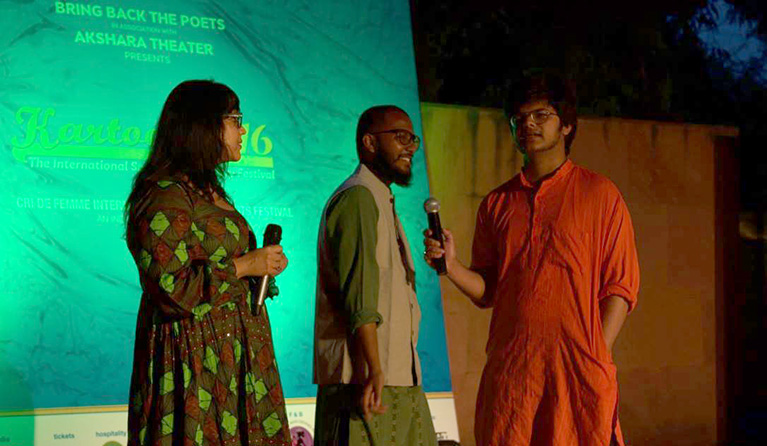

Aditi Angiras is a Delhi poet and activist who believes that poetry is politics. She founded a spoken word poetry collective called Bring Back the Poets that engages with gender, sexuality, and politics in the city and the country.

In March this year, Bring Back the Poets organised an international spoken word festival called Kartoos, which brought together Indian collectives and artists from other South Asian countries and the U.S.A. The collective has been part of student-led movements such as Occupy U.G.C. and Pinjra Tod. They host Extremely Queerious Poetry twice a year to provide a platform for spoken word engaging with gender and sexuality.

Read on for excerpts from an interview with Aditi about the collective, Kartoos, and writing and performing spoken word poetry—

Aditi Angiras: “After hiphop, discovering spoken word was almost inevitable.”

You said that when you discovered spoken word poetry, it felt like coming home. Do you remember whose work and what spaces first made you feel this way?

Home is where you go when you run out of homes. I think that comes closest to what I think a home means for me. I’ve lived in over a dozen houses, makeshift homes, moved around a lot but still always managed to find a room of my own. That is where I’d always find myself when I didn’t know where else to be, and what I’d do there was write poems.

I remember I was walking back home from the Chowraasta in Darjeeling when I heard ‘So this looks like a job for me…’ blazing over the stereo and it instantly arrested my attention. I was in class nine, I think. It sounds a little strange but I must admit Eminem brought poetry to me. My first years of writing were heavily influenced by artists like Eye-dea, Immortal Technique, Jean Grae, and other underground rappers.

After hiphop, discovering spoken word was almost inevitable. I was watching a lot of Def Poetry Jam videos, a series with feature performances by established rappers and spoken word artists. Then one day YouTube brought me to Andrea Gibson, her love poems and that honest voice that trembles. I think I fell in love with Gibson’s poetry and in love simultaneously. It was the beautiful winter of 2012 and I had just met this gorgeous person and we were on a date where they were making me listen to these songs they really liked and I started showing them these spoken word videos and I think that’s where spoken word poetry really found me. On that couch.

Nina Simone said, ‘An artist’s duty, as far as I am concerned, is to reflect the times.’ Does that ring true for you?

I haven’t ever consciously written with that intention. I mean I write love poems, and people across time and space have always felt love in similar ways. So I don’t know if I am writing something new. But I think it’s the language, the words that work like reflective wayfarers, where you see what’s there and the others see themselves in your glasses. We’re inventing words everyday. I write in slang, about everyday things, objects that did not exist a couple of decades ago. I mean, the way technology has taken over our lives, I think it has also changed what we think of love and how we express it.

Like they say, you can always taste your air in your water. Of course, there have been poems about the 2013 Section 377 judgement, the 2014 elections, about J.N.U., about the Panama Papers.

How do you work on your craft as a spoken word poet?

I always read out the lines in my head first and then mouth them to hear and feel how they sound and what they mean, and only then write them down. I am not a great performer—I have terrible stage fright even now—but I feel that the best way to see if a poem would work on the stage or not is to set it to music or set it on fire. When we’d be writing rap lyrics, one of the things was to always choose rhythm over rhymes. I still follow that rule. I think with spoken word poetry you’re always rewriting your poems with every performance, you’re always doing something different and something new. You sculpt your piece on the stage even if you write it down on paper.

Can you share a favourite piece of spoken word poetry with us?

One is too few to share; I’ll share two. May Be I Need You by Andrea Gibson and We Teach Life, Sir by Rafeef Ziadah. My favourite line from Gibson’s poem is: ‘I wrote too many poems in a language I did not yet know how to speak’. I like the video [of the performance] that has Robyn Aasmundstad on the guitar. That just adds a lot of feeling to the poem. That’s what I like about spoken word; it lets you experiment with other art forms. When I heard this poem for the first time it made me feel like I want to feel love like this.

Ziadah’s poem is so powerful, it changes you every time you hear it. It is so honest about life, about staying alive in difficult times and standing up for the things that matter.

When you perform poetry, do you find it makes a difference that the audience can hear a female voice and witness a female body along with the words of a poem?

At our first Slam Jams, most of the participants and audience were men. And, then gradually more and more women starting signing up. There was this one event where a friend shared a poem about child abuse and another about sexual harassment and public transport. And then this guy walked up to me and said, “Why are women always playing the victim? Why can’t they recite poems about things like the male poets were, you know about life, love, or something funny?” But spoken word also has a strong legacy of radical women poets and queer voices. So now, as the city is getting exposed to the art form, it’s also getting to witness a social change. At any spoken word event now, you’d see more women on stage. That’s a lot of progress from growing up in a city like Delhi, where I’d hardly ever come across a poet who was not a self-identified man at cultural events.

What have been some of the highlights of running an initiative like Bring Back the Poets?

When we organised the first Extremely Queerious Poetry Slam, we were anticipating only a handful of people in the audience as this was one of the first ‘queer’ poetry events in the country. But some 100-120 people showed up and we did not have the space to seat them. The event ran for over three hours and it all worked out well. That’s what made me realise that maybe the city is ready to hear and dance in step with our voices.

“Bring Back the Poets has stood in solidarity with and performed at numerous activist gatherings and cultural evenings at protest sites.”

How has Delhi as a city shaped Bring Back the Poets?

It is only through Bring Back the Poets’ relationship with the city have I forged my own. I never felt that I belonged to Delhi or that Delhi belongs to me. I still don’t. But the way the city lives and sleeps over so much history, with its university campuses, protests, the heartbeat of national politics, I get the feeling ki agar kahi iss duniya main himmat hai too woh shayad yaha hai.

Bring Back the Poets has stood in solidarity with and performed at numerous activist gatherings and cultural evenings at protest sites. We’ve performed in the Hauz Khas Fort premises, in South Delhi cafés, on the pavement outside Regal Cinema, outside and inside the Parliament Street Police Station, in Paharganj, at Akshara, and in university campuses. Our poems have echoes here, if you listen closely.

Recently we were invited to talk about the connection between spoken word and social justice in Mumbai. I don’t know if we did any justice to that but I remember speaking a lot about Delhi, its poets and poetry scene. That this city has a heartbeat, it’s alive and aching with a life of its own and what beautiful muse but that?

What does 2016 look like for Bring Back the Poets? Is the focus of the collective still similar to when you started in 2014?

Bring Back the Poets started one evening when we were having chai and doing adda at my friend Amrita Bhasin’s newly-opened cultural cafe Fursat Se. And, we thought ki kiss din fursat se poetry padhte hai. Almost a decade ago I had started this online forum called Insignia Rap Combats on Orkut where young, aspiring rappers from India and Pakistan would write, share audio, collaborate, and ‘battle it out’. After I abandoned the project or rather felt that I had done my bit for rap, I moved to poetry. I wanted to start something similar but this time do something offline, something I could be into physically as well. That is what Bring Back the Poets’ Slam Jams were in 2014. I will confess, I didn’t have a vision of what it was going to be or what I wanted it to become at that time. It evolved on its own and people who shared a similar politics became a part of it. By 2015, we realised we’re a queer feminist collective of poets.

The focus has shifted from just organising open mic events to creating Kartoos, an international spoken word and music festival. We’re also working on other such initiatives and international collaborations. The plan is also to conduct workshops across schools, provide mentorship, and setup a residency program.

How can interested poets sign up for your events? What are you looking for when you choose poets (if you do)?

We don’t usually choose poets, the poets’ poems choose us. If we’re organising an open mic event then there is a call for performers, where we ask the poets to send us a sample poem along with a short bio. Over the years, poets who have performed with us have shared our politics.

Our events are notorious for running for many hours sometimes. After the featured poets and the registered poets have done their poems, we usually ask the audience if anyone would like to read something. Then there’s always this one person who says they’d like to read a poem and this is their first time sharing their work in public. We welcome them with a round of applause to make them feel more confident and comfortable. We exhaust everyone, make sure everyone’s read every poem they wanted to read before we say goodbye.

Details about events and submissions are regularly updated on our Facebook page.

What’s next for your own writing?

I feel that for me, the next few years are going to be about collaborative art projects and writing. The last two years have taught me who else you have to be to become a poet. I’ve spent most of it organising, networking, meeting poets from around the world. While it’s got me where I am now, I guess it took away from me the time to seriously write. I am not a very prolific poet, poetry comes to me only in moments. I can only write poems that make me sick (literally) if I don’t write them and the first draft is the final draft. Now, I am spending a lot of time going back to those poems, rewriting and editing them, just putting them together into a manuscript.

Fiction isn’t my first language but I am thinking of picking it up. I am collecting stories for a someday book of short fiction. I see a lot of young queer women writing and performing poetry now, but I haven’t been able to get my hands on many short stories or novels by Indian queer women, except for Parvati Sharma and a couple of them in Too Close, Too Soon.