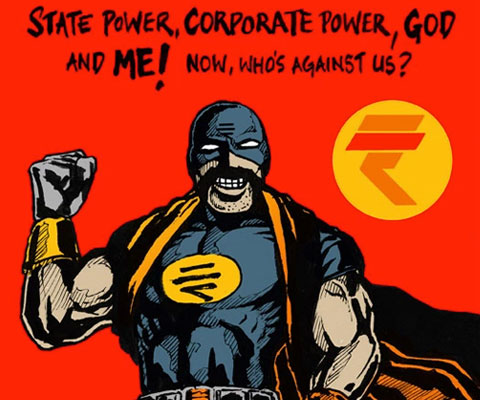

H. L. Mencken, in typically acerbic fashion, skewered the concept of democracy as being “heroically absurd […] incomparably idiotic, and hence incomparably amusing”. Ninety years later, this still holds true, judging from the political shenanigans we’ve all witnessed in the first four months of 2016. It is also a fitting description for Rashtraman, the 100% shuddh desi superhero created by Appupen, a.k.a. George Mathen.

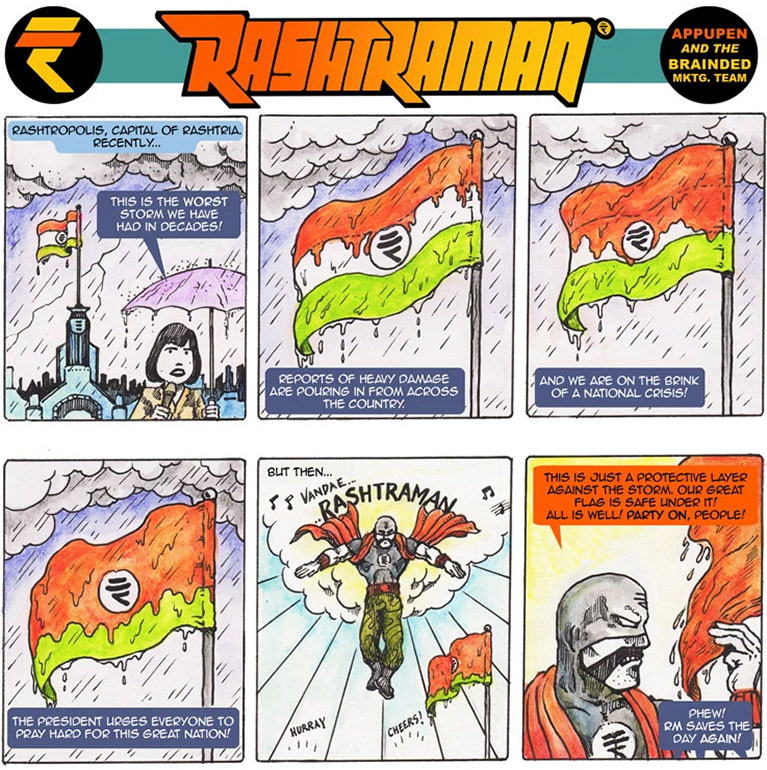

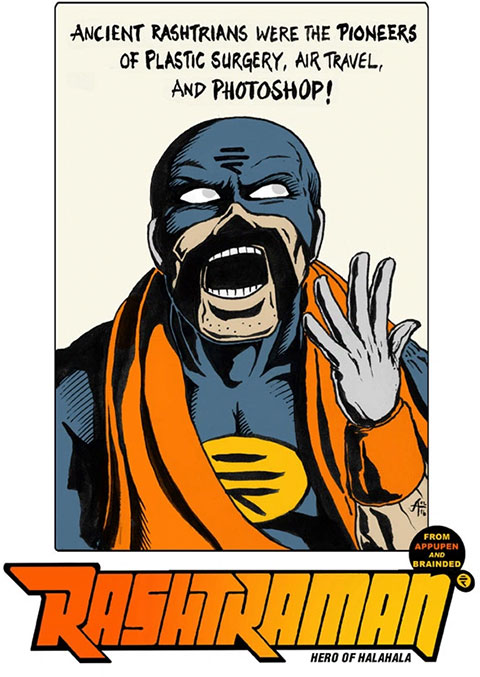

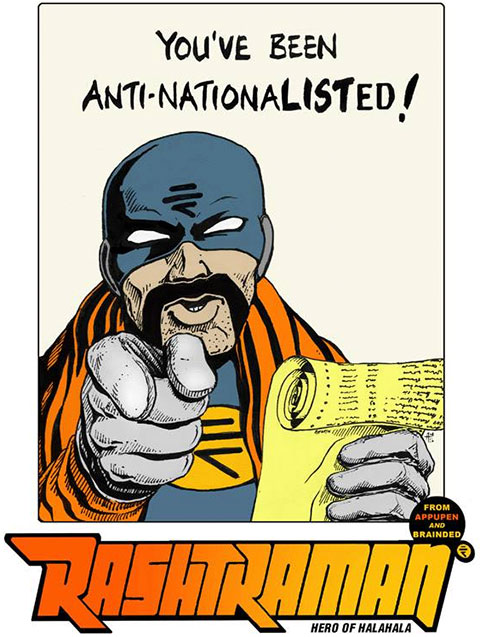

Rashtraman is the grand personification of the “extreme, barely sane type of nationalist” that George Orwell tried to warn us about. Superheroes have always been enthusiastic about promoting propagandistic views of national self-identity. This is also the narrative that Rashtraman follows, upholding “the Rashtria way” in a grim and ironic distortion of superhero ethics. To quote Batman’s Jim Gordon, he’s not the hero we need right now, but the one we deserve.

Rashtria is a fictitious nation located within the world of Halahala, an alternate dimension created by Appupen in the graphic fiction works of Moonward, Legends of Halahala, and Aspyrus. The presence of this doppelgänger reality allows Appupen to take aim at materialistic ambitions in stories of dystopia and social satire. Until now, his mode of attack has been deliberately oblique; silent, cryptic, and concerned mainly with existential issues. In sharp contrast, Rashtraman debuts a new style for Appupen, using vivid colour and wry commentary to take on everything from vigilante extremism, to overly aggressive forms of proselytising, and the jingoistic support of a certain kind of culture and a certain government’s actions.

Currently, George is releasing Aspyrus with French publisher Presque Lune while simultaneously prepping the work he will be presenting in May through the Goethe Institut at the 2016 Comics Salón in Erlangen, the leading comic festival in the German-speaking world. Following that, he says he’ll likely “bum around Hamburg and Berlin for a week.”

We spoke to George in an exclusive interview about Rashtraman and his other work. In the conversation that follows, flashes of his acid wit are in evidence when he discusses ideology versus realpolitik, quotes Chomsky, brings up Escher, Giger, Dali, and Picasso as influences, and at one point, ruefully explains that “even with the political news, before you can spoof it, they’ve already done a spoof on themselves.” Read on for excerpts—

George ‘Appupen’ Mathen. Photograph by Arun Kale.

Previously, you’ve said that you aren’t an activist and aren’t out to make a political statement. What prompted you to release Rashtraman right now? Did you feel that the time was right to say something?

I was working on this BrainDed spoof material that I had already sent out to a lot of publications in October and November last year. Nobody wanted to print it or put it out, so I put it up myself on my own platform for people to check it out. The thought behind that was, when you are putting out graphic novels, it is very expensive and people don’t read them. It’s just the term ‘graphic novel’ too… you keep it on a shelf and so now you are sophisticated, and you are cool because you have a graphic novel. Very few people really get into and are lost in the stories, like how a comic book follower would follow it. I’m a comic book fan; I collect comics and make them so my outlook to it is maybe a little different. The whole Halahala parallel world is something like that.

You clearly know the tropes and clichés of the world you are observing, so even if it’s not overtly political, it’s still saying something.

What’s the function of the artist now? I get the grant from I.F.A. to make my book, so there is something for art to do in this whole setup, but you know, like, art for beauty or just visually beautiful things, that’s a bit of a luxury right now. There are so many things we need to talk about.

If you are into, or want to pursue art right now, you have to take a stand. An artist is commenting on society and what’s happening, and in order to comment you have to have some idea of what’s going on. There’s a bit of responsibility—it’s not just growing hair and a beard and being dirty, that’s not the whole artist thing anymore. The message is always coming out if you see something that’s happening.

Rashtraman was made like that, and when the whole J.N.U. thing happened, I had a feeling that if you are not putting it out now, you might never be able to put it out after this. When a situation comes along like this, it’s a question to the artist at that time: will you take a stand? See you’ve already made it, it is sitting with you, do want to wait for it or put it out now? I think I made the right call. It was just to face myself better the next morning, that’s all.

Yes, particularly this year…

I think they’ve had this extreme right-wing meeting somewhere, where they made the decision that this is the year they’re just going to go all out. Earlier they used to make excuses, now there’s no cover-up, nothing; they’re just openly like: ‘This is how it is. If you don’t like this, you can leave the country.’

Especially now that we are trying to export the concept of “Make in India”.

It’s a very savvy thing that we are facing. They’ve obviously planned it out, with a business in mind—who benefits and for how many years. It’s been planned out quite nicely. I don’t want to give [them] credit, but it’s scarier like this.

The corporate nexus has to be highlighted because somewhere down the line there has to be some accountability from the creative people who work in advertising, or people who work in these big companies. The people who work for big companies should report that a company is doing this kind of stuff. If a big company is developing software for government surveillance without it being passed in Parliament, then somebody from that company should raise the alarm, say that we’re already developing this, and the government has signed a deal worth crores with us without having it passed anywhere else. If things like that happened there would be much more clarity.

If things like that happened, don’t you think that, as with Snowden, they might be made an example of?

They have to cover it up like that. Nobody wants to take direct responsibility. For example, I can’t get enough people to read my comics. Some people are not in the right atmosphere, so they might enjoy Rashtraman but they don’t want to put it out, or they don’t want to share it because they are in circles where it’s not the norm. I have many friends who have a problem talking openly about certain issues because they are a part of an advertising agency or campaign. There are big advertising firms supporting goon-looking fellows, like that M.S.G. guy. He’s got this food range coming out in competition with Patanjali. I mean, does he know it can also be read as monosodium glutamate? And M.S.G. is all natural products, a whole bunch of very natural products and… noodles. I mean, we Indians just love our noodles, we want our noodles. I just made an illustration with these two fellows, their beards are becoming noodles.

That sounds quite trippy, like some of your comics in Rolling Stone Magazine.

Hey, thanks! You should trip on them, nobody does and they feel very left out.

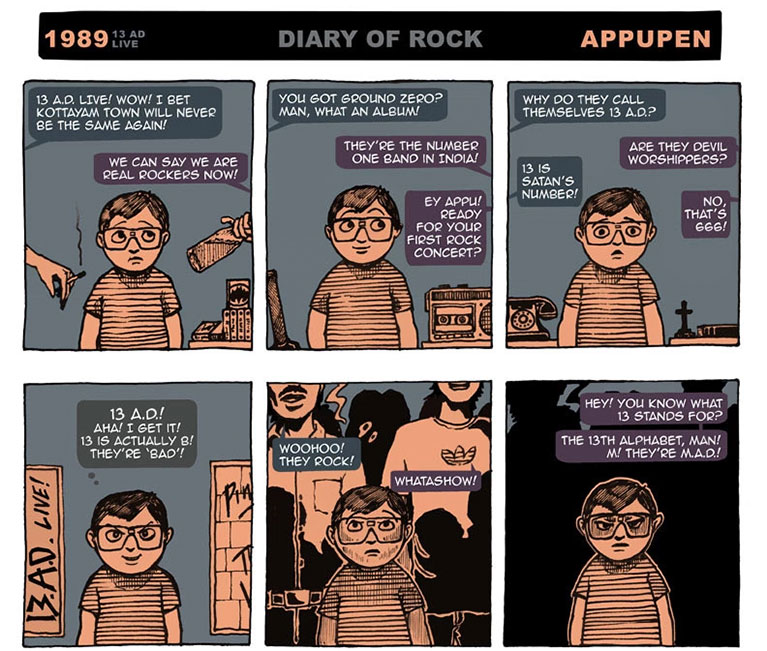

Diary of Rock felt deeply personal.

With Diary… see, I’m a rocker. I did my time, I play the drums; I’ve been manically collecting rock stuff from the time I was in school. Now over the last five or six years, actually from the end of Lounge Piranha, I’ve been thinking: what is this music scene out here? Because all of us grew up with these big bands, and the big record labels pushing them. We only got to hear the ones that were actually pushed by the record companies, we only heard what was actually on cassette or C.D., and we paid lots of money for it.

Diary of Rock by Appupen.

The experiences told through Diary of Rock are particularly Indian. The perspective of a rock fan in India is not the same as that of a rock fan anywhere else.

It’s about that Indian journey. We’ve never had an all-out rock scene; we knew these people who were rockers on the fringes of society, and people would say they were on drugs and all that. Then by ’99, we got Deep Purple to come to Bangalore, so that was like, a victory for all these fellows who were walking around with their long hair. Simultaneously, it was the death of the record industry with the coming of the Internet. By the time we woke up with the rock scene and the touring schedules, the main setup had gone dead and even they didn’t know how to push it.

Artists can charge for merchandise and live shows, but record sales are not there anymore. Then you’re talking small scene and small communities of listeners—how much are you going to do? So when I sit down and question it, it didn’t answer itself for me. I can accept that yeah, I went on this ride and I enjoyed it. It was never very thought out and it never promised that it would reach anywhere—you liked the attitude or the style of it, the way it was packaged for you; it was perfect and you went for it.

If you go back and start thinking of rock starting as a revolution, as rebellion, and then you see the kind of rock that we got here through the record companies, that was where we lost the essence of rock. So the Indian rock scene has to be treated differently. I’ve seen enough, so I just try to put it out in short snippets now.

Like the jokes about the Indian bands and how they function, I know a lot of people like that.

Yeah, it’s all different people’s ideas of this painted picture of rock that was sold to us, so how we interpreted it in our context was so funny. There are many jokes like that, so yeah, I will continue it.

At the end of Aspyrus, you do give a hint about Heroes of Halahala, which I assume is the book that Rashtraman is going to appear in?

Actually, no; Rashtraman came after that. They were a bunch of silent stories that I am working on; that’s another book. I started working on Rashtraman as an idea in September and October last year, which was quite a while after the book. The Heroes of Halahala stories are being developed, but it will come later because there is another book that I am working on, which has taken over.

Can you tell us more about the book that has taken over?

It still doesn’t have a final title. It’s called White City; I have been working on it for a year now.

Oh yeah, White City. I thought you might have been done with it by now.

It’s a little heavy on the work front, a little more demanding. I have taken up a style that was a little tougher in the beginning. The thing with that is that each page is a full drawing and no panels, so we’re trying to tell the whole story through full-page drawings. I really want to concentrate on each page as a composition.

Your readers have witnessed the evolution of your style. Going through Aspyrus, there are these full-page entirely black panels that serve as a visual break; within comics, you are always thinking about the elements from the last panel that the next panel will have and this just broke the whole chain.

If you think about the pacing of the story, that black break over there, we had to give that pause for the effect of that moment—the monster’s mouth closes over the girl and we see her scared expression. Thakk! It’s closed its mouth and it is darkness. We ourselves have been transported into that mouth. It’s the fear that everybody has that you can connect with easily, that dark closed space.

That’s a very cinematic effect; does that come from your work in films in Bombay?

I haven’t really worked so much in films as faffed about (laughs). I’ve helped some friends and been part of projects just to understand what was going on, but my project is still… I guess it will come out sometime.

There are a few touches that clue you into Halahala somehow originating from some kind of alternate-dimension Bombay. Was that intentional?

Bombay was very influential, yes. A lot of things were taken from Bombay. I wanted to show some of the extremely crowded parts of Halahala, where even though you don’t see the people all the time, the clothes and things jutting out and surging out of the houses shows that these places are really crowded. That’s a very Bombay thing—every window has an extension and on these extensions there are these plates and things lying around as though there’s no place inside, right? It brings a sense of urgency into the drawing when you do that.

I realised I was drawing Bombay things a long time ago, and definitely even in White City, there are all these crowded areas with little windows, with clothes hanging. I miss Bombay. I really like it, but Bangalore allows me to work without distractions, there’s nothing interesting happening most of the time (laughs).

In Rashtraman, just the use of colour was amazing because you are not such a “colour” guy.

I like colour but in the books I haven’t really used it. It used to take a lot of time for me to draw well enough to use colour simply. Rashtraman is small strips so I can do that. The book that I am working on uses a lot of stark black and white and very little red, so maybe that’s why the colour is coming out, and why Rashtraman suddenly took off in water colour. The first few stories were made like that.

Yes, especially in the one with the bleeding flag.

Yeah, everyone’s seen that one online; it will be printed sometime later. My eye is decent but my hand is not—yet. I’m still working on it. The eye catches things faster and the eye can tell. I’m still trying to catch up on my style. With the new book, I’m quite happy with the look. I was in a bit of a hurry to put out books out earlier, even though at the time I put it out, I thought I’d done the best job I could possibly do. Six months after a book comes out, I always look back and think, I could have put in more effort or done something more with it.

“The eye catches things faster and the eye can tell.”

Do you feel that people expect a particular style from you?

People don’t expect anything from me (laughs). I’ve tried to make a style, which is why this book took some time. For six months I was just making sure that the whole book can be in a steady, uniform style, but I don’t intend to stick with that style. Halahala is not a definite world that I can draw. It is a world that changes according to the story that you are telling. It’s the perfect fantasy world for stories. I don’t have to put a city or a mountain range permanently over there, it is kind of a dimension for stories that keeps adjusting itself to whatever the needs of the story are. That’s how I justify my not having a fixed style as well.

I know you’ve said a few times before that the comic scene in India isn’t really a scene. How do you think the questions of production, publishing, and distribution should be addressed?

It’s a business-driven world. If we have to make them notice us, we have to show them that we can make money. It’s because of this buzz around graphic novels that the business side of publishing believes that there is a future in graphic novels; that things are generally going to move towards becoming picture-heavy. That doesn’t mean much for the market, because as you said, it isn’t growing the way it should have. I just think more people have to work harder at what they are doing and want to come up with something, that’s the way it has come up in other places. There are these dedicated fuckers who sit and make great stuff. We need more of those; we are not very disciplined that way.

Right now, the artists that I know, they can’t concentrate on anything; they are all over the place. It’d be nice if a lot of them learned to be serious about finishing something. The college kids that I meet are enthusiastic about delivering their final project when they are in college, but after that, there is no project they are delivering on their own. If it’s a client project, they have to finish it for the client. So there’s a portfolio of client projects, but there isn’t one thing they have done for themselves. Maybe it’s because of the pressure to get a job, or make only those things that bring us money. It’s a larger question that needs to be addressed.

Did you face a lot of these questions yourself?

Rajeev Raja told me that if you want to be an artist you have to get out of the advertising office in less than a year. The office stays in your head all the time—that’s what they are paying you for. You’re going to go home and think about that fucker who’s going to take your job, or that other guy who emailed C.C.-ing five people for no reason, just to show that he’s doing his job. Shit like that is going to come back to bite your ass. We come to art with the intention of producing some message of our own. We need to sit and figure out where to put our efforts, or what is your life’s work.

How do you explain to your family that this is what you do?

I do work on commercial projects once in a while, so I manage to get by. I just don’t fix myself permanently to these people. I’ve figured out that it is a big waste because the moment you go out and pitch, you are at a disadvantage.

Now that you have a lot more creative liberty to work on the things that you want to, do you find that you want to revisit the animation idea that you were originally planning for Moonward?

Right now, I’m thinking of stuff that I can do myself, maybe mix and match visuals, and paintings and things like that. When I started making things, I wanted to make everything clean, like you see in big-budget Hollywood movies—you know when you see work, you can tell if it’s a big budget production or an indie production right? Now I am leaning more towards the indie way of making things. Maybe when I’ll make my Rashtraman movie, I’ll do it.

When you are sitting down to work, do you outline and work off a script or do you work it out while you are drawing it? What’s your process like?

For Rashtraman, there are six panels. I have to get as much punch out of those six panels, so the writing gets pared down to the essentials otherwise it gets too crowded. It’s a nice exercise to do when writing for comics; you have the task of cutting down content and saying certain things you are not trying to put into the drawings. I’m enjoying the process of writing for Rashtraman.

With other stuff, Diary et al, I like to approach the writing a little later, but if the idea of the story works you know whether it is worth spending that much time realising it. You know if it will have potential. I sit with my friend [Rahul] Chacko, we make ideas and I sieve out those we can attack and the ones we can leave.

Do you think collaborating with somebody creates a different energy?

Not entirely, the collaboration hasn’t been a complete success (laughs). I’m like a schoolmaster so I’ve been putting deadlines in front of Chacko and he’s been repeatedly not meeting deadlines (laughs). We’re working on many things together. I know him for a long time, so it’s not like I’m pissed off with him. If I’m working with him, it’s because I know that he’s a talented artist and a good critic.

Do you see yourself doing more gallery shows in the future?

I’ve shown some comic art and canvases in Bangalore and Kochi. I like to sell prints to comic fans or people who actually read the books. Selling to art investors is different, some socialite having your work, so that it can be worth 10 times more 10 years later, and become more “valuable”, so she can keep selling it to other socialites and eminent people who go to each other’s houses and say, “Ooh you have this artist too, wonderful!” I mean, you have to become this thing that they want to collect; you have to convince them you will be worth much more in 10 or 15 years. You have to do the social rounds and it’s just too much of a game; it’s too contrived.

Do you think comic art is considered a lesser art form?

I want to tell stories, and I make the page to tell a story. Later if it gets sold I’m happy. If I make the page and sell it as a single page, then I might as well make only single pages and sell it, why do I have to create a book? I try to stay true to the storytelling aspect of it. The gallery thing is a completely different ball game. Famous comic artists have their collectors and fans, who can buy their original art at whatever price the gallery sets. It’s a nice scene, so good for them. I’m not there (laughs). I don’t really see myself getting there anytime soon, so we’ll worry about that later.

If someone took offence to your comic would you stop producing it?

It’s very easy to influence the masses, to urge them to do anything in this country. I think Rashtraman stays in a small section of the population, these powers-that-be think it won’t make any difference in the larger picture. I fear that things have been tightened to quite a level already, I am not sure we realise to what extent and where we are, because it looks like there is a very heavy agenda at play, and we are only seeing the tip of the iceberg. The comic is very heartfelt but I don’t know how long it can carry on.

How do you think you would respond to someone claiming Rashtraman has offended them?

(Mock horror) What are you talking about?! I don’t know. I don’t have a response. I know things are getting absurd, but I’m a little bit of dreamer too, so I haven’t really given that scenario much thought. You are expressing something in order to bring something to life; you are using humour to highlight certain points, or to show the absurdity of certain things. That’s all I know how to do right now. I’m not the guy out on the street with a flag or a gun; I’m the guy at home with a pen.