Eschewing all the usual clichés about how once upon a time Sunday morning meant B. R. Chopra’s Mahabharat on Doordarshan and how it was so much more viewable than Ramayan, let me pose you a question: do you remember how non-dramatic the background score of Mahabharat is?

I recently started watching the repeat telecast of the show and I was astonished at how little background music there is. When it is there, it is usually subdued, but there are also long stretches when all you hear is the actors talking and maybe some ambient sound.

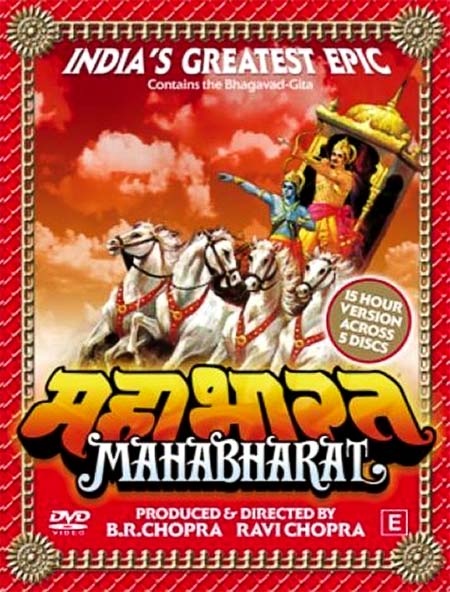

B. R. Chopra’s epic Mahabharat.

When I think about it, of course, I understand why I am so astonished today. At least for the last 12 years, we’ve only known Hindi shows that are shrill with dramatic background scores. If a husband betrays his wife, there’s a rising score that tells us we should be feeling shock and dismay. If there is romance brewing between a boy and a girl, there is that lilting music that shows us how very adorable the scene is. And if you’ve ever had the misfortune of watching a S.A.B. T.V. show, you’ll know that it is de rigueur in Hindi comedy shows these days to use canned laughter and odd squeaky noises that highlight ‘humorous’ dialogue you might otherwise have missed.

The point I’m trying to make here is that all these shows these days beat us over the head with their overemphasis on what we, the viewers, are supposed to feel. We’re told that this scene is funny, whereas that scene last night was sad. We’re no longer treated as intelligent beings, capable of understanding the few lines of dialogue and subtext in any scene.

While watching Mahabharat, on the other hand, I found myself marvelling at how well-made the show is. This is an old show (made in 1988), mind you, and obviously the costumes are ludicrous and the sets are hideous. However, the story isn’t dumbed down. You’ll find the same moral and ethical questions on the T.V. show as you would in the text. To give you an example, in one of the key scenes which occurs near the end of the war, Gandhari wails to Krishna that he could easily have prevented the war if he had wished it. We, the viewers, know that too. Krishna offers no explanation other than saying that he had to let destiny take its course. Then, when Gandhari curses his whole clan, he remains silent, only saying that he won’t embarrass her by asking for her blessings while leaving, as that will put her in an awkward position. He then leaves, clearly stricken.

We’re all familiar with the story so we know that Krishna’s descendants do get wiped out eventually, if not as spectacularly as the Kauravas and the Pandavas. Yet, we ask: Krishna is God, so why didn’t he stop the disastrous events from unfolding? And then we realise that the question is answered at the beginning of every episode by the famous ‘I am Time’ exposition. Of course, Time is all powerful. It is, in fact, the most powerful force of nature and it marches on regardless of anyone’s inconvenience. The curse has been spoken and has been recorded by Time and even the mighty Krishna cannot erase it now.

In another instance, Duryodhana approaches the pyre that the Pandavas have just built for their newly-discovered dead brother, Karna. He declares that he is the only one who has the right to light his friend’s pyre, and when the Pandavas protest, he asks Arjun: When you killed Karna, did you kill your brother or my friend?

In that simple question, one of the major philosophical questions of the Mahabharata is laid bare—that of blood ties and loyalties. The scene also reminds us that there’s no such thing as ‘pure evil’. Today, when we tend to view this Indian epic purely as a religious and moral text, this show reminds us of how foolish we’re being. Black and white, hero and villain are not as clear in this great poem as they are in our moral science textbooks.

So, circling back to where I started this column, what the Mahabharat rerun made me realise is how frankly awful Hindi T.V. shows are today. They’re loud, melodramatic, unsubtle, and so very, very long (to put this in perspective, I should mention that Mahabharat wrapped up in 94 episodes). I won’t even talk about the execrable Kahaani Hamaaray Mahaabhaarat Ki except to point out that the spellings in the title are enough to show exactly what has become important on Hindi television today. And yes, it’s not the story.

I think the most brilliant aspect of this series was the script and dialog by Lt. Rahi Masoon Raza. His study of Mahabharata was immense and he wrote a brilliant script for the series.

Definitely! The dialogues are perhaps slightly overblown, but that is understandable considering the epic-ness of the show.